[Bayesian Statistics] Basics

This post is a gentle introduction to the field of Bayesian Statistics focusing on its difference from the traditional frequentist statistics.

In the following series of posts, we will be talking about Bayesian Statistics, which is arguably one of the most probable field of applied statistics in 21st century for its practical and intuitive framework of quantifying the uncertainties.

Just like any other field of study that is built upon mathematics, Bayesian Statistics is also filled with heavy amount of mathematical formulas and proofs, and I don’t want to be overwhelmed by them. For this reason, I will try to keep the rigorous mathematical proofs as minimum as possible and rather try focus on the insight and the intuition Bayesian statistics can give us.

In latter posts, a renowned PPL (Probabilistic Programming Language) pymc3 made for python environment will be used to actually implement algorithms for Bayesian inferences. As a first post of this series, we’ll begin by talking about some of the fundamentals that differentiates Bayesian Statistics from traditional statistics.

1. Defining Probability

What is probability? Defining probability is the very first step in statistics as it is a field of study that tries to quantify the uncertainties in our lives by making use of probabilities. One definition of probability is “numerical descriptions of how likely an event is to occur”. Although this definition might sound trivial, formally defining “likeliness of an event” (don’t get confused with the likelihood in statistical sense) isn’t actually that simple. Let me introduce three different perspectives on defining probability.

- Classical Definition:

- Events that are likely to yield the same outcome have the same probability. For example, when tossing a coin, heads and tails are equally likely to show up and thus probability is 1/2 for each.

- This is a primal definition long before the advance of statistics in 19th century.

- Frequentist (Classical Statistics):

- Assuming infinite sequence of events, probability is defined as the relative frequency of each events. For example, by infinitely repeating the tossing of a coin, heads and tails appear half&half.

- By this perspective, definition of probability is consequential and this can sometimes contradict to our intuition (common sense) when we cannot assume infinite replication of events.

- For example, we want to know whether it will rain tomorrow or not. Considering these binary outcomes, the probability is either 0/1 (it rained / it didn’t rained). Why? - because we can observe “tomorrow” only once.

- Bayesian:

- Accounts for subjectiveness in the probability as long as it satisfies the basic axioms of probability.

- Compared to frequentist’s definition, interpretation of probability is way more intuitive and flexible (ex. The probability of rain tomorrow is 0.73).

- We can provide exact probabilistic answers to questions that were unanswerable in frequentist paradigm. (ex. What is the probability that Korea will be unified in the next 10 years?)

This might sound confusing, but the keyword here is that Bayesian’s probability is subjective. So when I ask “What do you think is the probability that COVID-19 will end in 2022?” the answer will likely to be different depending on people because each of us have different beliefs and concerns about this virus. Even if it’s not clear for now, we’ll talk more in detail in a moment and so hang in there!

Then how exactly are we going to calculate probability in Bayesian sense? Here’s a good news. In Bayesian Statistics, a single theorem solves everything! Let’s take a look at Bayes’ Theorem.

2. Bayes’ Theorem

Bayes’ Theorem is defined as the following:

Let’s try to interpret its meaning.

- Left side of equation: probability of event A happening, presuming that event B had already happened.

- Right side of equation: probability of event A and B happening at the same time divided by probability of event B happening.

From this equation, if we marginalize the numerator of the right side we have the following equation:

The implication of this equation is that we can derive a particular conditional probability (left side) by marginalizing the joint probability into a conditional and marginal probabilities. In a Bayesian sense, this conditional probability on the left side is called as the posterior and the numerator on the right side is each called as the likelihood and the prior while the denominator is evidence.

These three components - posterior, likelihood and prior - are the building blocks of Bayesian Statistics. In fact, the probability I mentioned to be calculated in Bayesian inference refers to posterior. Let’s consider a simple example and see how it’s done.

3. Frequentist vs Bayesian

For illustration, we will consider the following situation.

Q. We have a sack which contains fair coins and unfair coins (fair coin meaning probability of heads and tails is equal). We sampled a single coin from this sack and we want to know whether this coin is fair or not. So we filpped the coin for 10 times and the result was 3 heads and 7 tails. Under this situation, can we say that our sampled coin is fair?

Frequentist

First, let’s try to solve this question by frequentists’ approach. Like I mentioned earlier, frequentists assume a repetition of event and it is clear that consecutive tossing of a coin follows binomial distribution. To be more specific, this example follows binomial distribution $B(n,p)$ where $n$ (number of repetition) is equal to 10 and our goal is to make inference on the unknown parameter $p$.

In frequentist paradigm, we have to define an estimator $\hat p$ to make inference on the true parameter $p$ (for more information about estimators check out this post). There are several ways of defining an estimator, and for now let’s use the most commonly used Maximum Likelihood Method to derive $p$ analytically.

Maximum Likelihood Estimation in short, is assuming that our parameter is some unknown but fixed constant and trying to find the value that has the highest density in the probability distribution of events (likelihood) and use it as an estimator on behalf of the true parameter. In other words, considering our example, it is equivalent to finding $p$ that maximizes the binomial probability density $n \choose x$ $p^x (1-p)^{n-x}$.

Since our main topic is on bayesian we are going to skip ahead to the conclusion, but note that analytical solution for our example is relatively trivial in that as binomial density is a concave function, we can just set the differential equation to 0 and solve it to get the answer. Anyways, if we do the math then our MLE (Maximum Likelihood Estimator) is $\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i}{n}$ which is a sample mean of the number of heads.

In conclusion, for our example we derived MLE of $p$ to be the sample mean, which is $\frac{3}{10}$. This indicates that if we toss the coin infinitely many times, the probability of heads is only about 30%, meaning that this coin is somehow biased (for more sophisticated justification we normally conduct Neyman Pearson’s hypothesis testing) . Anyhow, we can conclude as the following:

- Considering our observed results, the coin is not fair.

This seems to make sense, but don’t you think it is a bit too irresponsible? The result is pretty lame and obvious. There’s not much of a new information gained by doing the inference in the first place. This is because frequentists consider parameter $p$ as a deterministic variable (fixed constant). Since there is no space for variability in the conclusion, the result is either fair / not fair. These two constrasting state of outcome can’t co-exist at the same time. With this in mind, let’s take Bayesian approach and see how it is different.

Bayesian

Now let’s take a look at Bayesian’s answer to our example. To find out whether our sampled coin is biased or not, we have to conduct a Bayesian Inference and as a first step, we need a concept of prior. Here’s what it is.

- Prior literally means our external prior knowledge about the subject. It can be some objective findings of rigorous research papers or it can just be our subjective beliefs on the topic.

- For example, let’s say that I’m interested in the probability of raining tomorrow in Seoul (today is Feb 09). Since I’ve lived in Seoul for a long time, I know that it is very unlikely to rain in early Feburary. So for this problem, I would say my prior probability of raining tomorrow is 0.1.

Likewise, for our example we can integrate any sort of our prior knowledge about the coin such as its physical properties (like there is a little crack on the coin) into our inference. Because of this flexibility in the inference, Bayesian Statistics can give realistic probabilities to questions that were hard to answer under Frequentist’s framework.

But always keep in mind that we shouldn’t abuse the use of priors. As Bayesian probabilities are innately subjective, we need some sort of formal justification of our priors for our inference to have credibility. I think we’ll have more time for that in the future and for now let’s move on to how Bayesian Inference is done based on priors.

Here are the steps:

- Set prior based on our external knowledge about the problem. (If we don’t have any knowledge we use uninformative priors, which will be discussed in the upcoming posts)

- Use Bayes’ Theorem to update your prior based on observed data (likelihood).

- Derive posterior.

To put it simply, a full bayesian inference consists of 3 elements - prior, likelihood, posterior. Let’s follow the steps and actually derive the posterior analytically.

<Step 1>

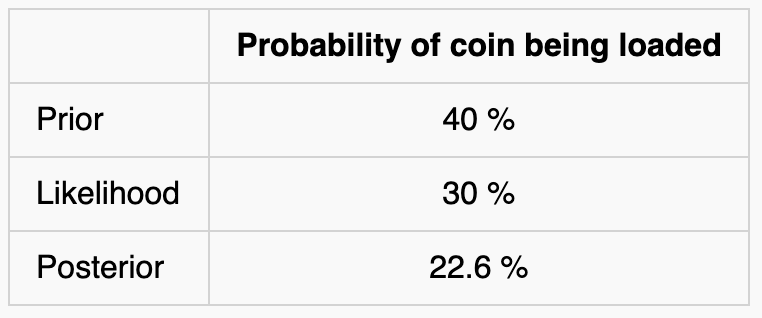

By inspecting our sampled coin carefully, I’ve found out some small cracks on the edges of the coin. I suspected that these cracks will have influence on the coin’s fairness so I decided to set my prior probability of this coin to be fair as 0.4, a little less than 0.5.

<Step 2>

Based on our observation of 3 heads and 7 tails, use Bayes’ Theorem to update our prior.

<Step 3>

Note that $I_{fair}$, $I_{unfair}$ are indicator functions. Since we have observed 3 heads, let’s plug in the value and calculate the posterior probability.

The result of the bayes theorem suggests that given our observed data, the posterior probability that our sampled coin is fair is only about 22.6%, which is enough to derive the following conclusion:

Considering our observed results, our coin has probability of 0.226 to be fair.

This conclusion, in contrast with that of frequentists, explicitly suggests a specific probabilistic statement about the amount of uncertainty in our inference (remember that from frequentist inference the conclusion was just “The coin is unfair”). Thus it’s more intuitive and informative. This is also in line with our common sense that our prior belief about the coin being fair 40%, was decreased to 22.6% after we saw an actual outcome of 30%.

Can you see how the probability was updated? One of the cool part of Bayesian Statistics is that we can also update the derived posterior by another observation. Let’s say that after this observation, we have conducted another set of coin tosses and got only 10% of head this time. If this is the case, our posterior probability will further be decreased from 22.6%.

This sequential updating makes Bayesian Inference flexible and informative. However, life isn’t so beautiful in practice. Above example was a really simple case where we could use binomial distribution, which makes the math easy for us to handle, where in real life situations it is often impossible to derive the posterior analytically.

Luckily, there is a way to address this problem by using our cutting-edge computers! We will talk more about them in detail in the following posts. This is end for now and it the next post, we are going to take a look at conjugacy of distributions.

References

- Gelman et. al. 2013. Bayesian Data Analysis. 3rd ed. CRC Press