[Bayesian Statistics] Modeling and Monte Carlo Estimation

This post is an introduction to how Monte Carlo method can be used for Bayesian models.

Previous Posts

1. Bayesian Statistics - Basics

2. Bayesian Statistics - Conjugacy

Review

Let’s briefly review what we’ve been doing so far.

(a) Conditional probability

(b) Joint probability can be marginalized into a specific event.

(c) Using (a) and (b), we have the following Bayes’ Theorem.

(d) 3 key elements of Bayesian Inference

- Prior: preliminary knowledge on a subject (can be subjective)

- Likelihood: observed data

- Posterior: updated result

In this setting, Bayesian Inference can be thought of as updating a prior belief based on a newly observed data using the Bayes’ Theorem. In previous post, we have seen how it can be performed analytically using the conjugate prior. However, we have faced a dead end as the denominator of the Bayes’ Theorem, normalizing constant, is often practically impossible to be derived by hand.

Hence as an alternative, we will be using computer simulations to indirectly derive the posteriors by using a statistical method known as Monte-Carlo estimation with algorithmic simulation technic known as MCMC. In this post, we’ll take a look at the bayesian modeling procedure and Monte-Carlo method as a buliding block of MCMC.

Statistical Modeling

Statistical Inference is a decision-making procedure which makes use of statistical models to enhance the validity of the result. This applies to Bayesian as well, so we first have to make a rough sketch on what statistical model is.

To put it formally, statistical model is a mathematical structure that can effectively imitate the data generating process of a given phenomenon. According to Karl Pearson, an English mathematician and biostatistician who pioneered the discipline of mathematical statistics, observations are merely random realizations from the true underlying probability distributions. This idea encourages us to see the forest instead of individual trees, allowing us to get a more profound and genuine understanding of the outcomes.

In general, the objective of statistical models can be summarized as the following list:

- Quantifying randomness (ex. confidence interval, estimator)

- Making Inference

- Hypothesis Testing

- Prediction

Unlike machine learning models where its primal focus is on the accuracy of the result, statistical models try to explain why and how the given results appeared, even if it means allowing some bias (inaccuracy) for the sake of reproducibility (variance). This is formally called as bias-variance tradeoff.

In Bayesian Inference, we use the posterior distribution to draw our conclusions about our questions. Once we manage to find the posterior distribution, we can reproduce lot of important statistics such as the moments and quantile values and so on. A very promising aspect of using this kind of Interpretable or White-Box model is that the results are fully explanable. It’s like having a blueprint! It allows you to understand and explain why and how your model has produced the result, as opposed to Black-Box models such as neural networks.

Bayesian Hierarchical Modeling

Now let’s see how Bayesians implement statistical models for inferences. The very first step of Bayesian Inference is equivalent to finding the posterior distribution, and to account for complex real-world phenomenon, we generally use hierarchical models. This is nothing but simply stacking up step-by-step layers of parameters in a natural order that matches our intuition.

Let’s consider an example. Suppose we are interested in the following problem.

Goal: We want to know the average height of male students in Yonsei Univerity, which is assumed to be normally distributed.

In this setting, our goal is to find the parameters $\mu$ and $\sigma$ of our normal distribution $N(\mu, \sigma)$ (especially $\mu$). Let’s take a look at how the Bayes’ Theorem is applied in our problem.

We can see that the posterior is proportional to the product of likelihood, conditional prior and the prior. Note that we have separated $f(\mu, \sigma^2)$ into two parts because considering the joint probability distribution of two parameters can be costly. Regarding this situation, we can define the likelihood and the prior as the following.

- likelihood

- prior

We are assuming that the parameters are exchangeable and used Inverse Gamma prior, one of the most frequently used prior for variance parameter, for the $\sigma^2$. We further assume that the hyper parameters $\nu_0$, $\beta_0$, $\mu_0$, $w_0$ are given constants.

An important point to consider in this setting is that the parameter distribution of $\mu$ is defined to be conditional on $\sigma^2$, which is equivalent to saying that $\mu$ is inferred assuming $\sigma^2$ is known. Because the parameters have dependency on the order of which they are being evaluated, this model is called as the hierarchical model.

Fig. 1: Illustration of Bayesian Hierarchical Model

We are going to take a close look at the implication of the above illustration as we talk about the posterior simulation using MCMC in the future. For now, let’s see what we get if we use the above Bayes’ Theorem with respect to this setting.

Regarding this equation, the game is set if the distributional kernel in the second line of equation can be approximated to one of the standard probability distributions we know such as Normal, Gamma, Poisson and so on. However, getting a closed-form solution gets practically impossible as we want to make inference on complicated real-world problems in which we can’t use standard probability densities to describe them.

Thus, instead of struggling to find analytical solutions, we can take a roundabout, which is Monte-Carlo estimation. In the next section, we will see what Monte-Carlo simulation is and in the following post we will talk about how it can be applied in Bayesian Inference to indirectly derive the posterior distribution.

Monte-Carlo Simulation

Monte-Carlo simulation is an idea that tries to approximate the properties of a probability distribution by using sufficient amount of samples. For example, suppose we want to find the mean of a gamma distribution. Instead of deriving the mean analytically, we can draw lot of samples from the gamma distribution and calculate the sample mean to approximately estimate the true mean.

Let’s say we have \(\theta \sim \Gamma (a,b)\) and we want to find the mean of $\theta$.

1. Analytical Derivation

Hence if $a=2$ and $b=\frac{1}{3}$, we have our mean of 6.

2. Using Monte-Carlo Simulation

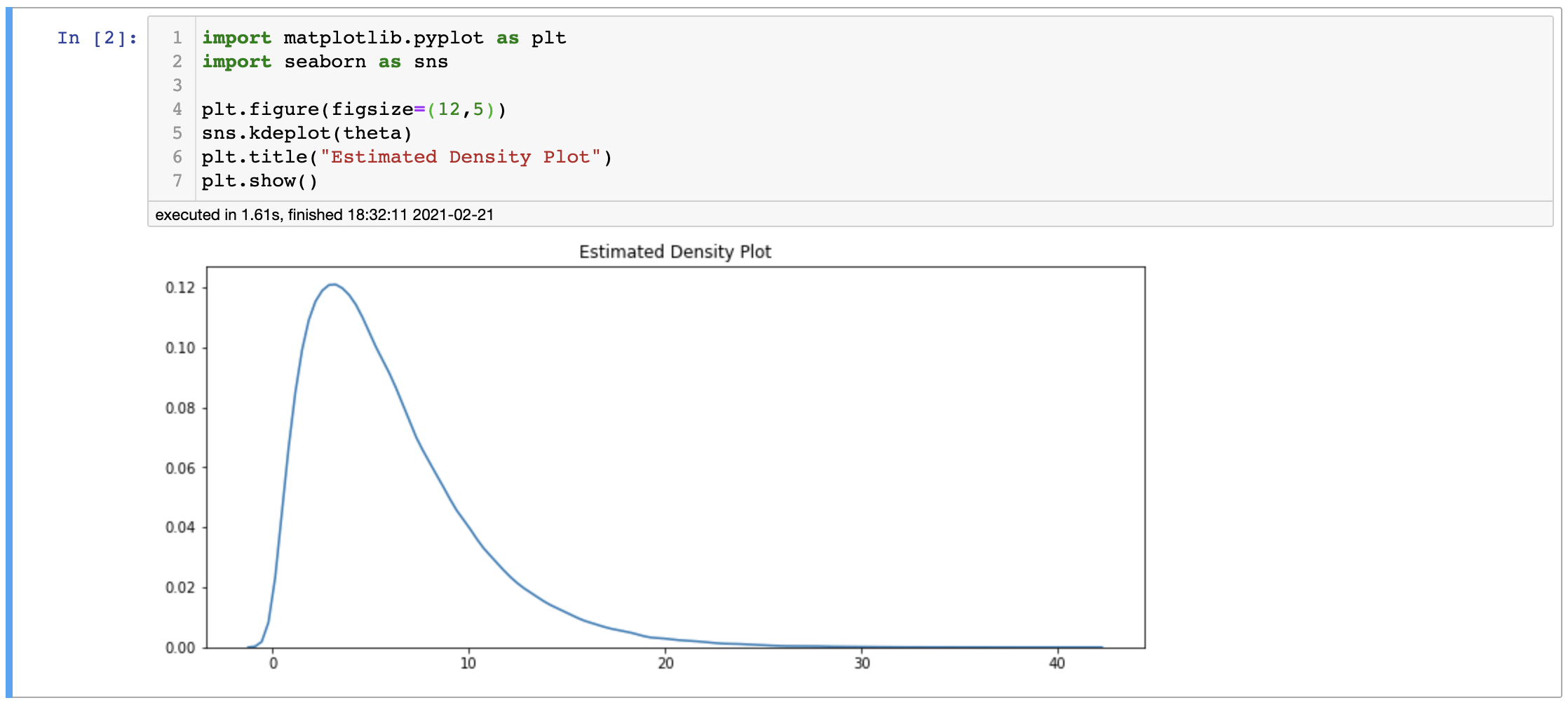

By using 100,000 random samples from $\Gamma(2,\frac{1}{3})$, we get almost the same result as 6. Moreover, we can see that the samples form a shape of the probability density of Gamma distribution. Why Monte-Carlo method works can be formally proved by using the Law of Large Numbers.

Likewise, as long as we have sufficient amount of samples, we can use Monte-Carlo simulation to make inference about the unknown quantities even if it cannot be derived analytically. This idea can be applied to deriving posterior as well, and the key point is how we can make samples without knowing the exact probability distribution. Luckily, MCMC has answer to this, which is the very next topic we are going to discuss about.

References

-

Gelman et. al. 2013. Bayesian Data Analysis. 3rd ed. CRC Press.

-

David Salsburg. 2001. The Lady Tasting Tea. Henry Holt and Company.